As far back as the first century, travellers to the Indian sub-continent wrote of the weaving of a fabric so fine that it appeared to have been woven with ‘threads of wind.’ In the 4th century, Megasthenes, Greek ambassador at the court of the Mauryan emperor Chandragupta, spoke thus of the courtiers: ‘Their robes are worked in gold, and they wear flowered garments of the finest muslin.’ The fine muslin that Megasthenes referred to, was hand-woven using a handloom technique called Jamdani, the essence of which has remained unchanged over thousands of years.

Jamdani was greatly favoured by Mughal royalty in the 16th and 17th centuries. Master weavers would bring gifts of the rare diaphanous fabric, carrying it through the streets in cases of gilded bamboo, before presenting it to the Emperor. It is said that on one occasion, the Emperor Aurangzeb reprimanded his daughter for not being adequately clothed. The princess replied indignantly that she was wearing seven ‘jamas’ or garments. So fine was the Jamdani fabric of her dress, that it was still transparent.

“Jamdani is so special and so rare a craft that it has been declared by UNESCO to be important to humanity’s cultural heritage and in need of preservation. ”

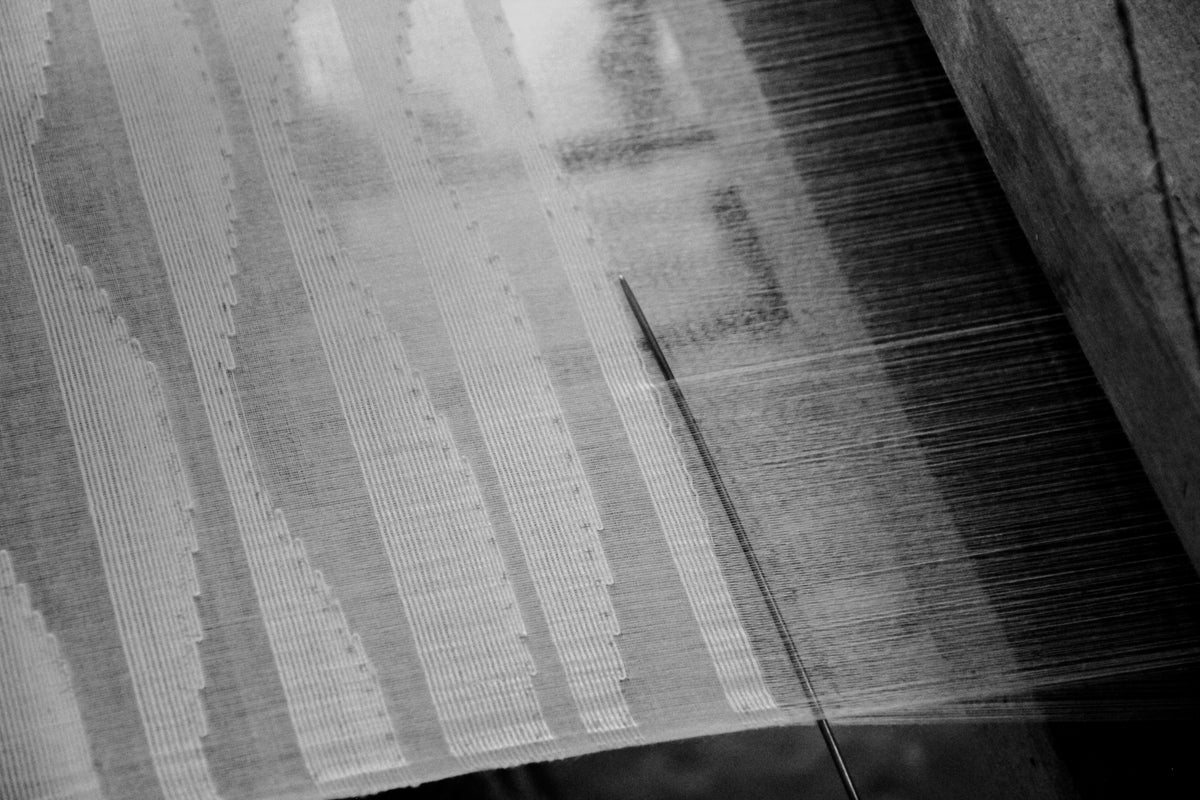

Today, among fields of golden mustard flowers, weavers in the eastern Indian state of West Bengal, work their looms in much the same way as their ancestors. Two weavers sit in a trench before a wooden loom, passing small shuttles of thread through the weft. The pattern is placed directly under the weaving frame and motifs are ‘loom-embroidered’ with great skill. There are no sketches or outlines. The main body of the textile is woven in unbleached cotton yarn of a very fine count while the pattern is created in a heavier, bleached, thread. The contrast creates the illusion that the intricate, opaque motifs are floating over the transparent background.

Quite unique in their subtlety and beauty, Jamdani fabrics are extremely labour and time intensive. It can take two craftsmen months to weave a small quantity of the delicately figured cloth. Jamdani is a 100% natural and biodegradable fabric. It is particularly eco-friendly because it is hand-woven without the use of electricity. It is a craft so special and so rare it has been declared by UNESCO to be important to humanity’s cultural heritage and in need of preservation.

“Varana’s Jamdani collection is as good worn to lunch at The Connaught as to the races at Ascot or gracing a sleek lined yacht”

Varana has worked with Jamdani weavers in Bengal to create a bespoke fabric, woven with a signature tonal wave pattern. The fine muslin has then been crafted into a discreetly luxurious line of resort wear described by Lucia Van der Post to be “as good worn to lunch at The Connaught as to the races at Ascot or gracing a sleek lined yacht”.